As part of my foray into learning about Ethereum, I started looking into the relatively new Proof of Stake supported Beacon Chain. The Beacon Chain is the main coordinating blockchain for Proof of Stake Ethereum and is currently running with the equivalent (in ETH) of ~$25 billion USD staked!

In doing so, I was surprised to see that there were regular reorganisations (or "reorgs") occurring on the Beacon Chain, so I decided to investigate to help learn more about the machinations of Ethereum and Proof of Stake. This article is a (slightly meandering) write up of my investigation into why reorgs happen somewhat regularly on the Beacon Chain. It also details some of my learnings along the way about ETH2 in general. If any of that is interest, stick around!

What Is a Reorg? Reorgs in a Proof of Work blockchain

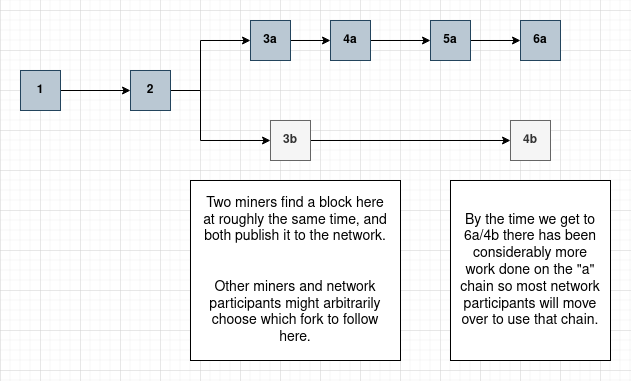

As a brief bit of background, in a Proof of Work block chain, such as Bitcoin or the current Ethereum main chain, reorgs occur most commonly because miners are effectively racing each other to mine the next block. When two (or more) miners mine a block at similar times the chain forks:

These forks are resolved by the fork choice rule that instructs clients to follow the fork with the most mining difficulty behind it (may also be known as the "longest chain" rule). The idea being that eventually a single fork will "win". This is a very simple way of forming consensus but has been shown to work well in Bitcoin, Ethereum and many other Proof of Work blockchains.

These forks are resolved by the fork choice rule that instructs clients to follow the fork with the most mining difficulty behind it (may also be known as the "longest chain" rule). The idea being that eventually a single fork will "win". This is a very simple way of forming consensus but has been shown to work well in Bitcoin, Ethereum and many other Proof of Work blockchains.

In this way, the blocks on the "losing" fork are referred to as "reorg"ed blocks as anyone initially following this fork needs to reorganise their chain after they learn that the other fork has "won".

On the Proof of Work Ethereum blockchain reorgs happen quite regularly. You can see a list of these reorgs on the etherscan block explorer but, at a quick glance, they appear to be happening at a rate of around 5 per hour. The rate of reorgs is a function of the block time, which is why they occur more frequently on Ethereum than Bitcoin.

The reorg depth is how many blocks deep the fork was before the fork was resolved. Just about all the time it's 1 here, which likely occurs similar the scenario above but where one of the forks is chosen in the next block and all miners stick to that fork from then on.

The reorg depth is how many blocks deep the fork was before the fork was resolved. Just about all the time it's 1 here, which likely occurs similar the scenario above but where one of the forks is chosen in the next block and all miners stick to that fork from then on.

If you're interested in learning more about reorgs in a proof of work blockchain, this article is informative.

Proof of Stake Reorgs

Proof of Stake works differently than Proof of Work in that in that validators (who are network participants that have staked ETH) are elected to create blocks, rather than needing to race to create a block. In Ethereum, a particular validator is chosen randomly to create a single block every 12 seconds.

Validators are rewarded with ETH for successfully creating blocks, so it is very much in the interest of a validator to have their proposed blocks included in the chain. The current reward for proposing a block that does get included is around 0.025 ETH at the time of writing (~$70 USD). There's a block proposed every 12 seconds and with currently around 308,000 validators, each validator will get to propose a block (on average, because it's randomised) every 42 days or so. So if you mess up and miss your slot it can be a while until you get another chance!

One reason a fork might occur is if a validator were to create and publish more than a single block when it was their turn to create a block. Validators are incentivized not to do this though, by the network "slashing" their stake if it can be proven that two blocks were created by the same validator for the same period. Looking at the list of slashings we can see that slashing occur much less often than reorgs (monthly instead of daily), so this is probably not usually the reason for the reorgs.

So then, assuming that proposers aren’t proposing multiple blocks and are attempting to act honestly, why are there still reorgs occurring?

A Super High Level Ethereum Proof Of Stake Overview

There's lots of better resources on eth2, but for the purposes of this article you should know that:

- Ethereum validators are people that have "staked" a large amount of ETH to be able to participate in the validating/proposing/attesting process. To actually perform these processes, validators run software such as Lighthouse, Prysm or Teku.

- Ethereum has the concept of "epochs" and "slots". Every epoch there are 32 slots and in each slot, a single validator is randomly chosen to create a block. Validators fill this block with transactions, and share it with the network.

- Validators are also assigned to "attest" to one slot each epoch. As part of this attestation, the validator will select what it believes is the head of the chain. These attestations help the network form a consensus on what the state of the chain is.

Investigation

To investigate, I ran my own Lighthouse beacon node and used the standardized ETH2 HTTP API to listen to new blocks and attestations being announced, with the plan to collect enough data to be able to understand more about why these reorgs were occuring.

Over the ETH2 API, the block data is of the form:

{

# the slot of the block

"slot": "3332233",

# the hash of the block

"block": "0x1dd45a53936a86a167e5e676dc52fef732290f45cd1ed861137ea4d7eba43646",

}

Whereas attestations are of the form:

{

# an aggregation of other validators who are attesting the same thing in the slot

"aggregation_bits": "0x00000000000000000000000400000000000080",

"data": {

# the slot of this attestation

"slot": "3338073",

# the committee this validator is attesting as part of

"index": "9",

# the attester's vote for the head of the chain

"beacon_block_root": "0x576513f60421f8aa0a4fa05bba137305cbe100cffac6afcf7c7822364b13fbff",

# (snipped some data around voting for "checkpoints")

},

# the signature of the attester - to prove that they really submitted this attestation

"signature": "0xa62ba00daa2096ed24242d358f775b729fa291c6f08dafd26e663cb83b8e7884c432850bc769e436250fb60e072cc43f01d64784aaee935b4bb395d6f9b16ddb26fce05f1bf4043bb3989f6336f3f18ad72b98a79684abee4b73b4cfc7c185bd",

}

For around 20 hours I ran a simple script that basically collected all the blocks and attestations published to the network along with their arrival time to my computer.

messages = SSEClient('http://localhost:5052/eth/v1/events?topics=block&attestation')

blocks_log = open('blocks.json', 'a')

attestations_log = open("attestations.json", 'a')

for msg in messages:

message = json.loads(msg.data)

message['arrival'] = round(time.time() * 1000)

if msg.event == 'block':

blocks_log.write(json.dumps(message) + "\\n")

elif msg.event == 'attestation':

attestations_log.write(json.dumps(message) + "\\n")

This collected 5912 blocks and 3418459 attestations.

Finding Reorgs

With the logged block messages, we can find blocks that are not part of the main chain with a simple algorithm that starts at the most recently collected block and works backwards, using each blocks parent. Any blocks that don’t get visited will be the reorged blocks. Because we're not doing this live, we can do this while being sure that our most recently collected block isn't t a reorged block itself (by manually checking this). In the live system, beacon chain nodes don't get this luxury as they can't see into the future!

def get_block_info(block_hash: str, bn_api_url: str) -> dict:

resp = requests.get(f"{bn_api_url}/eth/v1/beacon/headers/{block_hash}")

resp.raise_for_status()

return resp.json()

def find_reorged_blocks(blocks: list, bn_api_url: str):

"""

Finds blocks that aren't part of the main chain.

blocks: list of block objects, each with a 'slot' and a 'block' field

bn_api_url: url of the beacon node api

"""

block_map = {block["block"] : False for block in blocks}

# Assume the most recent block we have is the head and is not a reorged block.

last_block_on_chain, last_slot = blocks[-1]["block"], blocks[-1]["slot"]

# The list of blocks might have some missing blocks (because of

# interruptions in the data collection process) so we iterate until we're at

# the last slot we know about

min_slot = int(blocks[0]["slot"])

while int(last_slot) >= min_slot:

# mark this block as visited, it's on the chain!

block_map[last_block_on_chain] = True

block_info = get_block_info(last_block_on_chain, bn_api_url)

parent = block_info["data"]["header"]["message"]["parent_root"]

parent_slot = block_info["data"]["header"]["message"]["slot"]

last_block_on_chain, last_slot = parent, parent_slot

return [block for block in block_map if not block_map[block]]

Running this against my list of 5615 collected blocks I got the following blocks as blocks not on the main chain:

| Slot | Hash | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3345326 | 0xfc54ca25f7df62e9f3b24d8fb9fa6b21ec5bc2d312107ce29a48ba2d6b7188c3 | |

| 3344246 | 0xa3b0a48f6cbd0a7ca7e6337e4b939a146e2e91fa7f275ebf75dcaf0630b95ee6 | |

| 3344244 | 0x5862cb53788db14b989df390199d69aaebd694894183e152ccfae9bf0df283f6 | Marked as skipped beaconscan |

| 3343277 | 0xe2c00aabfc8d584d122518d32e58d8f317f6326205df9ed8b488486a971eef52 | |

| 3340911 | 0x6a1adc86f899d66ac8b0cd2848b03112d5a25da3f9feb3e3a320585c4535c683 | I never received this block but it's marked as reorged on beaconscan |

| 3342234 | 0x5d97817910ad60452dba75b3cf92890324194ec65bb2c2a0ac484f970b3280ca | Marked as skipped on beaconscan |

| 3340347 | 0x977491737cb0f60b6f5c1a21d5745162f9a649bc031f467a591a703613927e02 | |

| 3340161 | 0x4cc45ee812f161b6eb478e292b9cc19f05f7e954d6d158dd5a503acf734448ee |

Checking this against BeaconScan the list looks pretty good, with the exception of slot 3340911 which looks like it wasn't collected by my event listener. There were also a few slots that BeaconScan marked as skipped but I saw blocks for. These discrepancies are interesting, and potentially give a clues towards why these blocks were not included.

![]() Finding information about reorged blocks was actually kind of tricky because beacon chain node implementations seem to prune reorged blocks out of their block storage. This make sense to do as once you're certain that a block isn't part of the main chain it is isn't useful to keep around. However, it does make this sort of investigation harder! For finding parents of these reorged blocks, I relied on block explorers like BeaconChain to find the data.

Finding information about reorged blocks was actually kind of tricky because beacon chain node implementations seem to prune reorged blocks out of their block storage. This make sense to do as once you're certain that a block isn't part of the main chain it is isn't useful to keep around. However, it does make this sort of investigation harder! For finding parents of these reorged blocks, I relied on block explorers like BeaconChain to find the data.

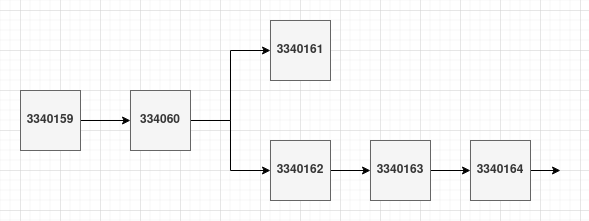

Slot 3340161

Starting the investigation by first examining the oldest reorged block: the block proposed at slot 3340161. This block has a parent of the block proposed at slot 3340160, however the block at 3340162 also has the same parent. From inspecting how this fork was resolved by looking at the state now, we can see that the end result of this fork was something like this, with the block at slot 3340161 being reorged:

My suspicion here is that 3340161 might have be sent "late" and wasn't received by the proposer of 3340162 in time. Looking at my log of blocks and their arrival time lends some credence to this theory:

{"slot": "3340158", "arrival": 1646905919766}

{"slot": "3340159", "arrival": 1646905932380}

{"slot": "3340160", "arrival": 1646905946542}

{"slot": "3340161", "arrival": 1646905964624}

{"slot": "3340162", "arrival": 1646905968938}

{"slot": "3340163", "arrival": 1646905981605}

{"slot": "3340164", "arrival": 1646905991401}

Which can be summarized as (reorged slot is bolded):

| Slot | Time from last slot (ms) |

|---|---|

| 3340159 | 12614 |

| 3340160 | 14162 |

| 3340161 | 18082 |

| 3340162 | 4314 |

| 3340163 | 12667 |

| 3340164 | 9796 |

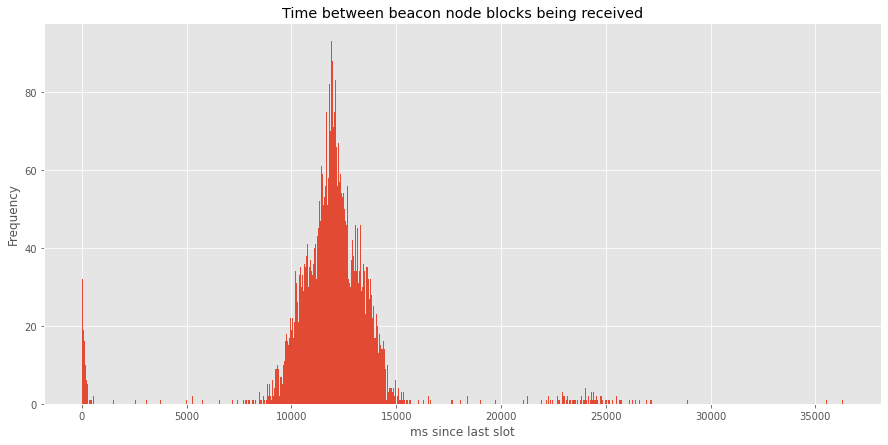

Blocks are supposed to be produced every 12 seconds, so I think you'd expect the delay between blocks to be around 12 seconds. Indeed, looking at a histogram of the time between received blocks, we see a big spike around the 12s mark.

This is, of course, only showing my particular view of the network and because of the distributed nature of the system, other nodes might be seeing very different message arrival times. Still, it's all I have to work with so I'll use my view of the network as an approximation of what other nodes would have likely seen as well.

Given that, it does make some sense that the proposer of 3340162 has built their block on top of 3340160 instead of 3340161. A validator knows it has to meet slot deadlines (remembering a new block needs to be produced every 12 seconds), so will start building it on top of the last block it has received and verified. In this case, it seems like this block was 3340160.

Once we get to the next slot, 3340163, the validator chosen to produce a block a choice to make. The validator has had enough time to receive both 3340161 and 3340162 and needs to pick which block to build this block on top of. So why did it choose to build its block on top of 3340162 and not 3340161?

Looking at the ethereum 2 beacon chain specification (that is written in Python! Executable specifications are pretty cool) for the fork_choice get_head function gives a clue:

def get_head(store: Store) -> Root:

# Get filtered block tree that only includes viable branches

blocks = get_filtered_block_tree(store)

# Execute the LMD-GHOST fork choice

head = store.justified_checkpoint.root

while True:

children = [

root for root in blocks.keys()

if blocks[root].parent_root == head

]

if len(children) == 0:

return head

# Sort by latest attesting balance with ties broken lexicographically

# Ties broken by favoring block with lexicographically higher root

head = max(children, key=lambda root: (get_latest_attesting_balance(store, root), root))

This code, as I understand it, will walk the chain until it comes to a fork. When it comes to a fork (like we have in the scenario above) it will choose the block that has the most attestation stake behind it.

Luckily we also collected attestations so we can try to verify this! But first some background on the attestation data that we collected: to decrease the network and processing load of thousands of individual attestations flying around the network, validators are divided up into committees to perform the attestations. Validators communicate their attestations to other validators within their committee, and select validators are selected to aggregate these attestations globally. These aggregations are stored in the aggregation_bits field of the aggregations messaged we received, so to find the total support for a particular head there's a little extra processing needed:

def calculate_head_attestation_votes(attestations):

"""

Takes an array of attestation objects (as returned by the Beacon API) for a

particular slot and returns a dictionary of head : number of votes

"""

# Mapping of: head -> committee index -> votes

attestation_aggregations_by_committee = defaultdict(lambda: defaultdict(int))

# Multiple attestations might have the same aggregation bits set, so we need

# to OR them together to avoid double counting

for attestation in attestations:

aggregate = int(attestation["aggregation_bits"], 16)

# This is what this attestation is voting as the head of the chain

head = attestation["data"]["beacon_block_root"]

# The particular committee this aggregation is part of

index = attestation["data"]["index"]

attestation_aggregations_by_committee[head][index] |= aggregate

attestation_head_votes = defaultdict(int)

# sum the aggregations to get the total number of votes for each head each

# bit in the aggregate represents a particular validator's vote

for head, aggregations in attestation_aggregations_by_committee.items():

for _, aggregate in aggregations.items():

attestation_head_votes[head] += aggregate.bit_count()

return attestation_head_votes

This code basically sums up the aggregations we've received so we can find the total support for each particular head. (I manually filtered out aggregations for individual slots with a little jq scripting: jq -c 'select(.data.slot=="<slot>")' < attestations.json > attestations_for_slot.json).

beacon_block_root here is what the validator is voting as the head of the chain at that point of time, so running this script to see how validators were attesting for the slots of interest.

First, looking at the attestations for the 3340161 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340160 | 5430 |

And then looking at the attestations for the 3340162 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340162 | 6384 |

| 3340160 | 36 |

| 3340161 | 7 |

| 3340122 | 2 |

| 3340156 | 2 |

These two tables are really quite informative because they show:

- In the slot that the 3340161 block was produced, there was not a single attestation for that block. All attestations were for the block in the previous slot.

- In the next slot, there are attestations for the 3340161 block, but there are a lot more for the block that was produced in the same slot.

Again the spec is illustrative in making sense of what might be going on here:

A validator should create and broadcast the

attestationto the associated attestation subnet when either (a) the validator has received a valid block from the expected block proposer for the assignedslotor (b)1 / INTERVALS_PER_SLOTof theslothas transpired (SECONDS_PER_SLOT / INTERVALS_PER_SLOTseconds after the start ofslot) -- whichever comes first.

So, we can probably reasonably guess that:

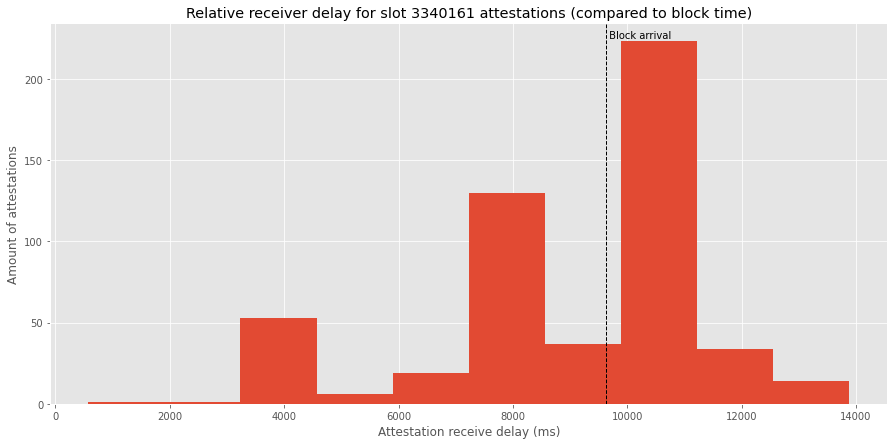

In slot 3340161 it's likely no validators had received the 3340161 block, so all attested that the head of the chain was the 3340160 block. We can plot the arrival time of the block compared to the arrival time of the attestations for this slot, relative to the start of the slot to make extra sure (again with the caveat that this only represents my view of the distributed network, other participants likely saw a slightly different view):

The dashed line here represents when we received the block for this slot, whereas the red bars show a distribution of when we received attestations for this slot.

The dashed line here represents when we received the block for this slot, whereas the red bars show a distribution of when we received attestations for this slot. INTERVALS_PER_SLOT is currently 3 so validators should wait only 4 seconds (12/3) before publishing an attestation if they haven't received the block from the proposer. There are, however, a considerable attestations received after a longer amount of time, which might be because of delays in me receiving the attestations or perhaps could mean that the validators aren't perfectly following the spec. It is curious that there's a big spike of attestations arrived after the (quite block) arrives but given that no validators seemed to attest to the late block, it seems likely that it might just be because of network delays.

In slot 3340162 we have a few different attestations for the head:

- Attestations for 3340162: these are probably validators that received this block before

SECONDS_PER_SLOT / INTERVALS_PER_SLOT. These attestations are essentially picking this block over the 3340161 block. At this stage, to these proposers, we can infer that both the 3340161 and 3340162 blocks have no attestations, as the fork choice rule says to pick the lexicographically higher root. - Attestations for 3340160: these are probably validators that didn't yet receive the 3340162 or 3340161 block so are voting for the last block they know about.

- Attestations for 3340161: I think these are validators that are, at this point in time, following the "3340161 fork". I think this might be because they've received this block and haven't received 3340162 or perhaps because they have received attestations for 3340161.

- Other attestations: Not really sure why these validators are voting for such old blocks as the head. Maybe they are experiencing network or processing issues and are really far behind?

Some other thoughts:

- I think that the 3340161 block being late is likely the reason that the attestations aren't split at all for that block - with that block being late, all validators effectively have an extra slot time to receive the proceeding block so can all agree it is the up to date head. There's also probably an element of luck involved, the next block has some fairly "wrong" votes in it.

- With ~312k current validators, there should be about 312k/32 = ~9700 attestations per slot. I'm not totally sure why I get a bit less than this amount, but I suppose it could be because my node couldn't keep up with the amount of attestations or perhaps it could mean that some validators were missed in the aggregated data.

- It's a little curious that we see 7 validators following the "3340161 fork". I suspect (but really have no way of checking) that these validators received an attestations for this block before they made their attestations. Maybe this is because some small set of the network was able to receive this block without much delay.

Overall it's pretty neat that the protocol is able to resolve and move past the the problematic late block, essentially by skipping over it!

Slot 3340347

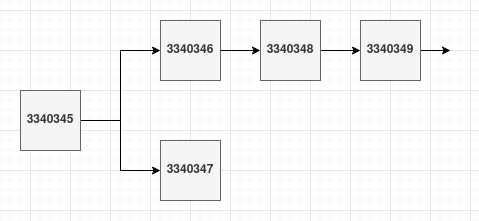

Lets then look at the next forked block, which was the block produced in slot 3340347. This fork looks slightly different to the last fork, in that the later block is the reorged block, not the earlier block:

Looking first at block arrival times:

| Slot | Time from last slot (ms) |

|---|---|

| 3340345 | 13304 |

| 3340346 | 22950 |

| 3340347 | 557 |

| 3340348 | 11481 |

| 3340349 | 13332 |

This is different to the previous case in that this block appears to have not actually been that slow to arrive, relative to the last block. The previous block was slow to arrive though!

Looking again at the attestations for the slots:

The 3340345 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340345 | 9667 |

| 3340344 | 2 |

The 3340346 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340345 | 7772 |

The 3340347 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340346 | 6063 |

| 3340345 | 4 |

The 3340348 slot:

Slot beacon_block_root vote |

Count |

|---|---|

| 3340348 | 4333 |

| 3340346 | 4 |

So the reconstructed timeline is:

- 3340345 is created on schedule and the vast majority of validators attest to this block

- 3340346 is created with some delays, no validators receive it in this block so all attest that 3340345 is the current head

- 3340347 is created, building off of 3340345, likely because the proposer didn't receive 3340346 in time. No attesters attest to 3340347 and instead all attest to 3340346.

- 3340348 builds off the head of the chain, which in this case is 3340346 as it has attestations whereas 3340347 does not.

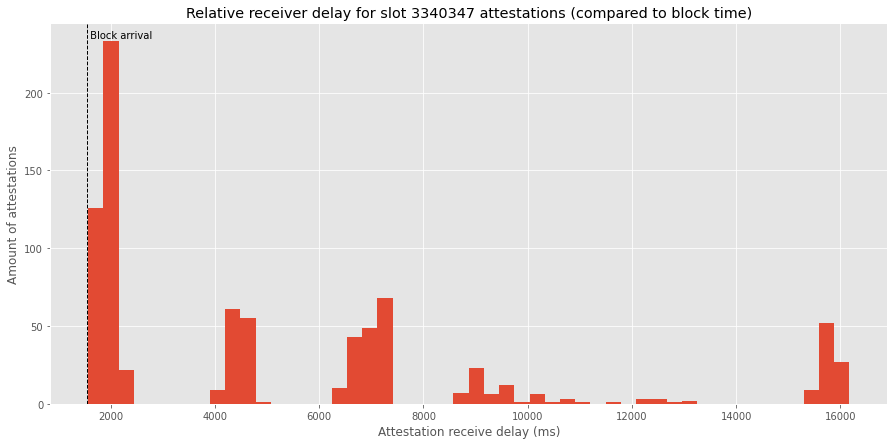

This is a little weird to me, I don't completely understand why at the 3340347 slot there was not a single validator who voted for the block produced at 3340347. I initially thought that this might be due to the block arriving later than it should, so plotted the arrival time of the block relative to the attestations:

This time the block is not later than the 4 second

This time the block is not later than the 4 second SECONDS_PER_SLOT / INTERVALS_PER_SLOT deadline, and it looks like the validators have waited for the block before sending out attestations.

Unfortunately, I don't have a good handle on why the network didn't choose the 3340347 block when choosing the fork to follow. Reading through the specification, the fork choice appears to dictate that this block should be chosen and even incentived to be chosen, through the proposer_boost_root mechanism that 'boosts' blocks that arrive on time.

In my understanding, the only reasons for this block to not be chosen are either:

- My view of the network was significantly different to what the rest of the network saw. Perhaps the 3340347 block was delayed for all other participants.

- The 3340347 block did not pass the filter_block_tree check. I believe this could have been because it had a different finalized or justified checkpoint to what the rest of the network agrees upon.

Unfortunately, with the data I have, I'm not quite sure how to definitively prove or discover which of the two options caused this block to not included in the chain. The contents of this block is (as far as I can find) no longer available, due to beacon nodes pruning it from their history.

The rest of the reorged blocks in my log seem to have very similar symptoms to this block, in that:

- The reorged block follows a delayed block

- The reorged block creates fork to be created, most likely because they didn't receive the preceeding block in time

- The network follows the earlier block instead of the later block

I think there most likely must be a possibility that I'm missing here as I don't think it's coincidence that these reorgs seem to happen under the same circumstances. It seems unlikely that each of these blocks were skipped by filter_block_tree or that my view of the network was considerably different to the rest of the network each time.

Conclusion

I learnt a lot about how attestation works on the beacon chain while investigating this, despite not completely solving the mystery of why exactly there are some reorged blocks.

To continue this investigation, maybe it would make sense to:

- Have more collectors logging data, possibly on compute instances geographically distributed. This should allow me to get a better sense of what the rest of the network sees.

- Log the contents of blocks, to better discover why nodes skip over them.

If anyone has any theories on what might've happened in the second reorged block (and the other, similar, reorged blocks), please let me know!

Update

Since posting this article the reason for this behavior was revealed thanks to a researcher the Ethereum foundation reaching out. It turns out, at the time this was written, Proposer Boost was not active on mainnet which was causing tiebreaks to be resolved through lexicographical ordering of the block hashes. Excerpt from the message I received from said researcher:

We've identified the reason for the reorg of block 3340347 - proposer boost is not yet active on mainnet. Proposer boost is a local fork choice change that does not affect consensus code (such as block validity rules or finality conditions), thus not requiring a soft/hard fork (forks have significant coordination costs across client teams & stakers). Clients are releasing it in their software at their own pace, and stakers can upgrade to software with this feature without a targeted timeline.

Without proposer boost, the fork choice tiebreaker is the block root (higher lexicographical ordering wins). The block roots were the following:

Block 3340346: 0xfaf0....

Block 3340347: 0x9774....

This particular reorg instance is explained by the lack of proposer boost, and the tiebreaker rule.

These "unfair" reorgs are probably a good rationale for having proposer boost turned on, so hopefully it is activated soon!