tldr: I created a mesh VPN networking tool named meshboi which you can checkout on my github! This post walks through the 'magic' behind mesh VPN tools, using meshboi as an example.

Mesh VPN tools, such as Nebula, Tailscale, Zerotier and Tinc, facilitate the creation of peer to peer (mesh) networks across the internet. These tools securely, performantly and transparently enable multiple distributed computers to communicate as though they were physically connected to the same network switch (layer 2 or 3, depending on the tool and configuration used). There’s lots of use cases for these tools, but some popular uses-cases are:

- Allowing services on instances across multiple clouds to communicate

- Allowing secure remote access to home networks for roaming users

- Bridging “home lab” networks with cloud networks

These tools enable this communication to occur transparently to applications that are sending and receiving packets over the mesh, while also working around common barriers in networking over the internet, such as firewalls and NAT.

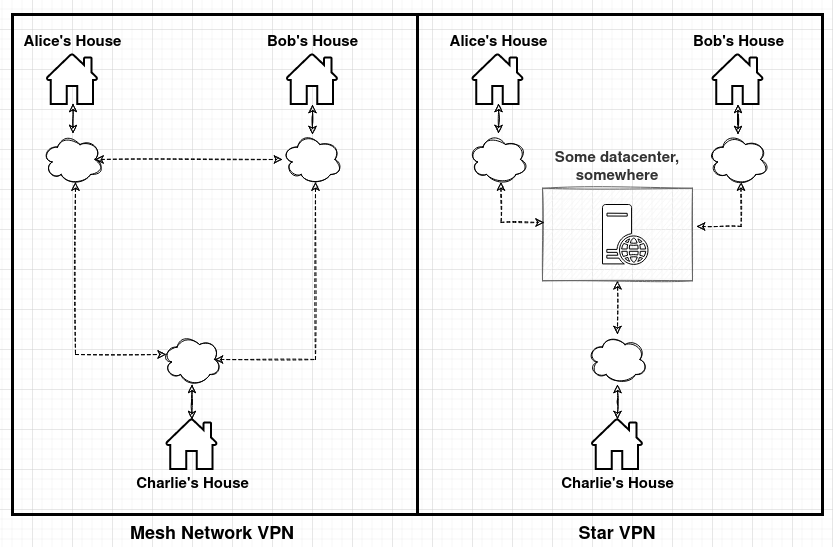

The mesh model is in contrast to traditional “star” VPN solutions, such as OpenVPN or StrongSwan. In a star VPN, traffic between peers needs to pass through a central VPN server, which increases latency and reduces scalability (the central server can only handle so much traffic). The image below shows a simplified high level view of the VPN types. A mesh VPN facilitates direct connections between peers, whereas a star requires connections to go through a central server.

It's worth making a quick side note on the use of "VPN" here. In this case, VPN is meant to mean a network of peers over the internet that can communicate amongst each other. This is different to “consumer” VPN products (such as NordVPN or Private Internet Access) that are used for privacy and/or to avoid geographic website blocks. For these VPN products, the VPN server is effectively used as a gateway for clients to connect to the broader internet through. Peers on these networks generally do not and cannot connect to each other. For the rest of this post I'll exclusively focus on the first kind of VPN, which lets peers communicate.

It's worth making a quick side note on the use of "VPN" here. In this case, VPN is meant to mean a network of peers over the internet that can communicate amongst each other. This is different to “consumer” VPN products (such as NordVPN or Private Internet Access) that are used for privacy and/or to avoid geographic website blocks. For these VPN products, the VPN server is effectively used as a gateway for clients to connect to the broader internet through. Peers on these networks generally do not and cannot connect to each other. For the rest of this post I'll exclusively focus on the first kind of VPN, which lets peers communicate.

Introducing.. Meshboi!

There’s a bunch of interesting problems to solve in creating one of these tools, so I thought it’d be fun to create my own mesh VPN tool to learn more about how they work. While there’s a lot of complexity in creating a mesh VPN that is secure, performant and works across 100% of network configurations, creating something that isn’t as robust, for the purposes of fun and learning, is definitely doable.

The tool I created is named meshboi and if you want to jump straight to the source code, you can find it on my github. Meshboi is written in Go and was created purely for the purposes of fun and learning (so please use one of the other fantastic tools for running production things on!).

The below asciinema recording shows a simple demo of meshboi, showing how it enables communication between two physically separated computers, both behind NAT and firewalls, that are only connected via the internet.

Why is this hard?

There are a few core problems to solve when creating a tool like this.

-

Discoverability/Bootstrapping - if two peers want to talk to each other, how do they know how to find each other in order to form a link?

-

Transparency - The tool should allow applications to send their traffic to peers on the mesh without needing the applications to be aware of any of the subtleties of being on a mesh. The tool should abstract away the concept of the mesh VPN, such that the applications do not need to be modified and can behave as normal network applications.

-

Network Address Translation (NAT) - The majority of the internet is still IPv4 based, so there’s complexity in allowing communications between two computers that are both behind NAT. In some cases, one or even both can be behind multiple layers of NAT (CGNAT).

-

Firewalls - Between any two pairs of computers, there’s typically a lot of firewalls that typically (and probably rightfully!) act to stop unsolicited network traffic from entering networks. While some of these firewalls are configurable, and could be opened up, in some environments the firewalls are out of the control of the user (think corporate network or wifi hotspot in a cafe). Some ISPs might even block certain types of traffic.

-

Security - If a tool is exposing a local network to the internet, it should make sure that traffic is secured so that it cannot be read or tampered with by third parties. The model that most of these mesh VPN tools use is that traffic coming in from the internet is not trusted, but once it is in it is trusted.

I’ll go more into the details of each of these problems, and how meshboi (and mesh VPN tools in general) solve them.

Discoverability

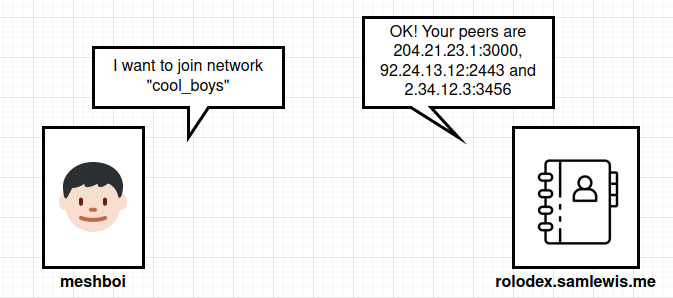

When a new computer wants to join a mesh network, it needs a method of discovering other computers that are already part of the mesh. This discovery process allows the joining member of a mesh to find internet addresses of other members, so that it can initiate the communication channel.

In theory, this initial bootstrapping could be done manually, through some out of band communication, like email or instant-messaging but this is not so practical and is further complicated by dynamic IP addresses, NAT and firewalls (discussed later).

Instead, most mesh network tools solve this issue by having a centralized server that members of the mesh talk to in order to get the details of their peers. In Nebula this server is named a “Lighthouse”. Meshboi also uses this concept and calls it a “Rolodex''. The Rolodex should be hosted on a server with an IP address that does not change, so that it can always be accessed by peers wanting to join the network.

It’s important to note that unlike centralized VPNs, no real traffic passes through the Rolodex. However, some tools do allow the data to be proxied through this server as a last-ditch option when NAT or firewalls are particularly hard to overcome. In Meshboi’s case this is not possible and the Rolodex server is completely ignorant of any data moving around the network.

It’s important to note that unlike centralized VPNs, no real traffic passes through the Rolodex. However, some tools do allow the data to be proxied through this server as a last-ditch option when NAT or firewalls are particularly hard to overcome. In Meshboi’s case this is not possible and the Rolodex server is completely ignorant of any data moving around the network.

The meshboi Rolodex serves only as a method to bootstrap networks, with peers directly authenticating each other (using dTLS and PSK as explained further on) before any data is passed between them. Because of this, the Rolodex implementation supports multiple completely separate networks. The Rolodex server is basically a very unsophisticated in-memory key/value store with {networkName: list<IP addresses>}. I'm currently running a Rolodex server on a personal VPS (rolodex.samlewis.me) that anyone can use to bootstrap their own networks but it's also possible to run a separate instance yourself on a server that's directly accessible to the internet.

Transparency

For a mesh VPN tool to be truly useful it needs to be transparent to network applications that send and receive data over the mesh network. The tool’s usefulness would be very limited if the source code of each application needed to be modified in order to know how to communicate with peers over the mesh.

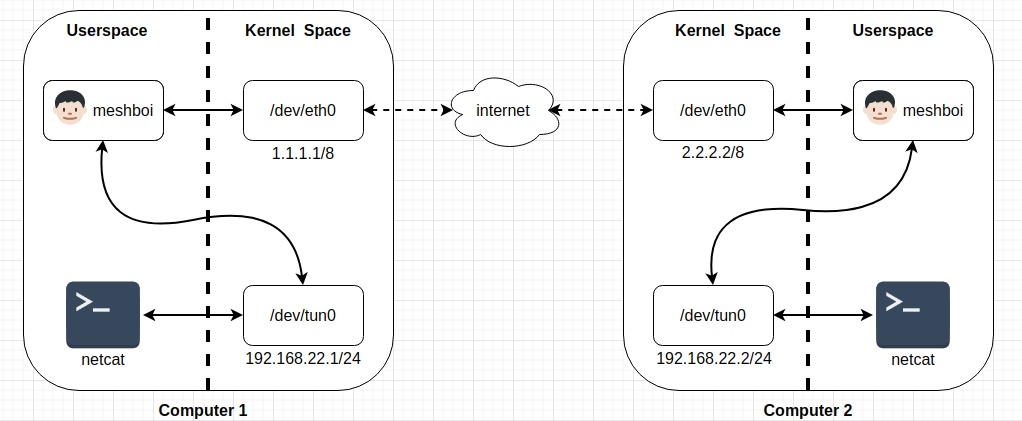

Mesh VPN tools solve the transparency issue using what is known as “tunneling” where the packet meant for one subnet is tunneled through a connection on another subnet (usually over the internet) and then injected into the subnet on the other side of the tunnel. On Linux systems, TUN/TAP devices facilitate tunneling in this way by providing virtualized software-only network interfaces.

Backreference has a nice explanation of TUNTAP devices:

"You can think of a tun/tap interface as a regular network interface that, when the kernel decides that the moment has come to send data "on the wire", instead sends data to some userspace program that is attached to the interface. In a similar fashion, the program can write to this [device], and the data .. will appear as input to the tun/tap interface.”

In this way, having a TUNTAP device with an assigned IP address on the mesh’s subnet allows applications wanting to communicate on that subnet to send data to the TUNTAP device. The data is then able to be read by the mesh VPN tool and forwarded over the internet to the corresponding peer.

In meshboi's case, the mesh network is a L3 network so TUN devices are used. Meshboi creates a TUN device at start up and assigns an IP address on the mesh's subnet (of the user's choosing) to it.

The diagram below shows, at a high level, how packets would flow between two mesh members running netcat (but this would look the same no matter which network applications were used - you can imagine NGINX running on one side and Firefox on the other, for example).

The details of what exactly the data being sent across the internet are further covered in the Security section below, but for now it's OK to imagine that it's a UDP packet that contains the original IPv4 packet. UDP is typically used for this tunneling use case as it does not suffer from the drawbacks of running TCP over TCP.

The details of what exactly the data being sent across the internet are further covered in the Security section below, but for now it's OK to imagine that it's a UDP packet that contains the original IPv4 packet. UDP is typically used for this tunneling use case as it does not suffer from the drawbacks of running TCP over TCP.

The following code snippet shows a (slightly modified for readability) snippet from the tun_router.go showing how this works for outbound packets.

for {

// Read from the TUN device, this reads out a packet destined for another peer on the mesh

n, err := tr.tun.Read(packet)

header, err := ipv4.ParseHeader(packet[:n])

// Find the VPN/Mesh IP that this packet is destined for

vpnIP, ok := netaddr.FromStdIP(header.Dst)

// See if we know of a peer with that Mesh IP address

peerConn, ok := tr.store.GetByInsideIp(vpnIP)

if !ok {

// Drop the data if we aren't aware of any peers with that address

log.Warn("Dropping data destined for ", vpnIP)

continue

}

msg := make([]byte, n)

copy(msg, packet[:n])

// Queue the data to be sent to the corresponding peer

// this will send the packet to their internet address

// through the dTLS UDP tunnel

peerConn.QueueData(msg)

}

The corresponding code for handling packets that have been sent by other peer members to us is handled in peer_conn.go:

b := make([]byte, bufSize)

for {

// Read a packet that another peer has sent us over the interneet

n, err := p.conn.Read(b)

// Write the packet to the TUN device so applications awaiting data from the mesh receive it

written, err := p.tun.Write(b[:n])

}

NAT & Firewalls

The majority of computers on the internet are behind both NAT and firewalls (sometimes multiple levels of both). Being behind NAT and firewalls adds difficulty in allowing external parties to talk into your network across the internet. For an average user this is typically good, as (unless you are hosting an internet accessible server on your LAN) you typically do not want random parties on the internet being able to initiate communications to computers/services running within your network.

However, this is a problem in establishing a mesh network. Members on the mesh need to be able to send arbitrary packets between each other. One way of solving this would be for each member to add port forwarding rules to their routers and open ports in their firewall(s). This is typically the appropriate solution to make a locally hosted server accessible on the internet and for a user with the technical know-how and access privileges this is doable (if kind of annoying). However this gets trickier and becomes a less ideal solution when you consider that users might be on a corporate network, using public wifi (for example at a cafe) or even behind Carrier Grade NAT.

Luckily there is another way! This method takes advantage of us knowing the peers that we want to talk to ahead of time (because the Rolodex has told us about them!).

Firstly, to explain the issues that NAT introduces in this context: NAT works by transparently translating source ports and IP addresses from a computer on a LAN to source ports and IP addresses from the internet facing side of its router. Typically, because this is done transparently, there is no need for anything except for the router to know what this mapping is. However, because we want to open a port and advertise what that port is to other peers it becomes necessary to know what the port is.

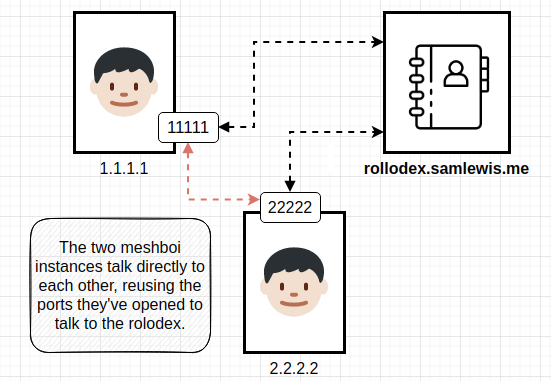

To solve this, peers on the mesh network reuse the same the source port that they used to communicate with the Rolodex in order to talk to their peers. This allows the Rolodex to store the IP address and port of each member that it sees from its perspective and send that to data to new peers. Assuming that the Rolodex is somewhere on the internet, this means that it has the “internet view” of each mesh member and can be the authority in sharing how to connect to each member.

The Rolodex server also serves as a way to ensure that the NAT mapping remains up to date. NAT devices will garbage collect mappings after an inactivity period (as otherwise eventually all the usable ports will be used up), so the Rolodex is used to send and receive heartbeat messages from peers to ensure that these remain valid for as long as the peer is running.

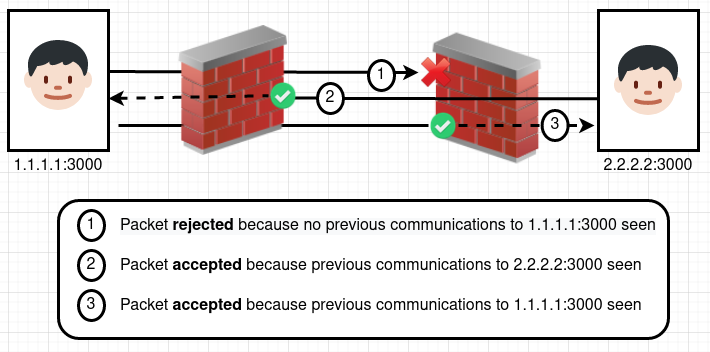

Great! But what about firewalls? As a very short intro, firewalls usually deny all incoming traffic unless it has been explicitly permitted. However, because of the way IP traffic works , for most users, firewalls need to be stateful. This basically means that the firewall allows incoming packets so long as it has seen corresponding outgoing packets. This is so that, for example, when you send a request to load www.google.com the firewall will allow the response from the Google web server. Without a stateful firewall, the firewall would need exceptions added for every website and IP address that a user expects to communicate with.

Meshboi (and most mesh networking tools) take advantage of this by having pairs of peers send each other packets in order to form a connection. As both sides have then "initiated" communications (in the view of their respective firewalls), the firewalls will then allow incoming packets from the corresponding peer.

For meshboi, as will be elaborated on in the next section, each pair of peers have one peer designated as the 'server' and one as the 'client'. The client will connect to the server immediately whereas the server only waits for the client to connect. For this reason, its only important for the server to send out a message to the client, to then enable the client to talk inward to it.

func (pc *PeerConnector) openFirewallToPeer(addr net.Addr) error {

conn, err := pc.listenerDialer.Dial(addr)

defer conn.Close()

// .. snipped error handling ..

// It doesn't really matter what is sent here - the important part is

// something is sent. We're effectively telling any and all (stateful)

// firewalls on our path to the peer to allow any future traffic that has

// originated from that peer

_, err = conn.Write([]byte("hello"))

// .. snipped error handling ..

return nil

}

I’d be remiss not to mention this excellent Tailscale blog post that goes into a lot more depth on the firewall/NAT problem and considers more than the basic NAT scenario that I considered here. It also has some very excellent diagrams! Worth the read if my explanation here isn't making sense or if you’re interested in the subject.

Security

As Mesh VPN tools tunnel traffic over the internet, they need some sort of security that affords protection against things like:

- Data being readable by third parties

- Ensuring that incoming packets are only accepted from trusted peers, not from malicious internet people

- Data has integrity (people can’t mess with our messages without our knowledge)

- Replay attacks

Tailscale uses Wireguard links for this security and Nebula uses the Noise Protocol Framework which is what Wireguard is built upon.

Not knowing much about this type of security (and admittedly, barely knowing much more now!), I initially naively considered encrypting each internet-bound packet transmitted by meshboi by using something like AES and a pre-shared key. However, while this would stop the data from being readable by third parties it wouldn't ensure protection against the other points above - attackers could still mess with the integrity of packets or could replay past packets.

That said, if we were certain that all the traffic over the mesh would already be in protocols that affords that sort of protection (such as HTTPS or SSH) then this sort of double protection would arguably be unnecessary. However, as meshboi should allow any sort of traffic to flow over its mesh it is better if it can guarantee some sort of security.

Because, as previously mentioned, traffic over the tunnel should be UDP, this somewhat limits the choice of protocols for implementing this security. To cut a long story short, for meshboi's case, I ended up using the not-super-popular UDP version of TLS: dTLS. To implement this I used the dTLS implementation in the Pion stack (which, as a complete aside, has to be just about the friendliest community I've ever encountered on the internet!).

Each link between peers in meshboi is implemented as a dTLS link. When peers learn of each other (via messages from the Rolodex) they will attempt to form this link using the pre-shared key they have been configured with. As dTLS requires the concept of a 'server' and 'client' for each connection, this is implemented somewhat arbitrarily in meshboi by using the peer with the 'largest' IP address to be the server:

func (pc *PeerConnector) AmServer(other netaddr.IPPort) bool {

ipCompare := pc.myOutsideAddr.IP.Compare(other.IP)

switch ipCompare {

case -1:

return false

case 0:

if pc.myOutsideAddr.Port > other.Port {

return true

} else if pc.myOutsideAddr.Port < other.Port {

return false

}

case 1:

return true

}

}

As well as using dTLS to ensure that every peer that attempts to join the mesh is trusted, meshboi also makes use of the PSK 'hint' feature to transmit some out of band information between peers. As far as I understand, the ability to send hints is to facilitate dTLS connections where there's a human in the loop that might need a hint to remember the PSK. In Meshboi, this is somewhat abused to send the internal VPN address of the peer:

func getDtlsConfig(vpnIp netaddr.IP, psk []byte) *dtls.Config {

return &dtls.Config{

PSK: func(hint []byte) ([]byte, error) {

return psk, nil

},

// We set the PSK identity hint as the IP address of this member in the

// VPN as an quick and hacky way of signalling (out of band) who this

// member is to other members we connect to. A more robust way of

// achieving this would be to define an OOB messaging scheme to do this

// with instead.

PSKIdentityHint: []byte(vpnIp.String()),

CipherSuites: []dtls.CipherSuiteID{dtls.TLS_PSK_WITH_AES_128_CCM_8},

ExtendedMasterSecret: dtls.RequireExtendedMasterSecret,

}

}

In this way, the messages sent across the dTLS link can be tunneled IPv4 packets that can be injected directly into the mesh network. A future improvement might be to change this so that the IPv4 messages are wrapped inside other messages with metadata, so that more out of band messages can be defined and sent between peers.

Performance

To test the performance of meshboi, I used iperf3 to check the achievable speed between a GCP e2-micro (2 vCPUs, 1 GB memory) Debian Google Cloud Platform instance and a Vultr $5/month instance (1 vCPU, 1 GB memory).

For comparison, I also tested Nebula, Tailscale and then opened up instances' firewalls to run the test without any tunneling/mesh VPN software at all. It's likely that the configuration could be improved for better performance with the other tools, but it's nice at least as a point of reference.

As these tools do networking and packet encryption/decryption in userspace, my benchmarking technique was to measure both the achievable throughput across a link and the CPU usage hit taken. To do this, I ran mpstat 1 to find the average non-idle CPU time while running iperf3 across the link. I ran the iperf3 server on the GCP instance and the client on the Vultr instance, and measured CPU only on the Vultr instance. My benchmarking technique is not very comprehensive and likely could be improved (open to hearing suggestions!) but I think gives somewhat of an indication of the difference between these tools.

| Test | Non idle CPU time (%) | Average Bandwidth (Mbps) |

|---|---|---|

| No tunneling | 2.74% | 253 MBit/s |

| meshboi | 75.47% | 98.4 Mbit/s |

| Nebula | 57.44% | 222 Mbits/sec |

| Tailscale | 72.02% | 183 Mbit/s |

As expected, meshboi is probably not the best choice compared to established tools! I'm sure there's lots of easy wins to be had here though, I suspect the choice of dTLS cipher could go a long way to speeding things up. Meshboi also copies data around somewhat unnecessarily which is also most likely slowing things down.

Conclusion

Hopefully this article gives a bit of an insight into how the magic of mesh VPN tools work. If you're interested in learning more then by all means feel free to dive into the meshboi source code, play around with meshboi or even submit a patch or two - there's likely boundless things to improve!

Otherwise, if you're after a production ready mesh VPN solution there's a lot of solutions out there that work much better than meshboi. In particular, solutions like Tailscale and Nebula can do things like:

- Multi platform support (OSX, Windows)

- Better authentication (cert based or SSO based)

- Have better performance

- General robustness

- Have audited security